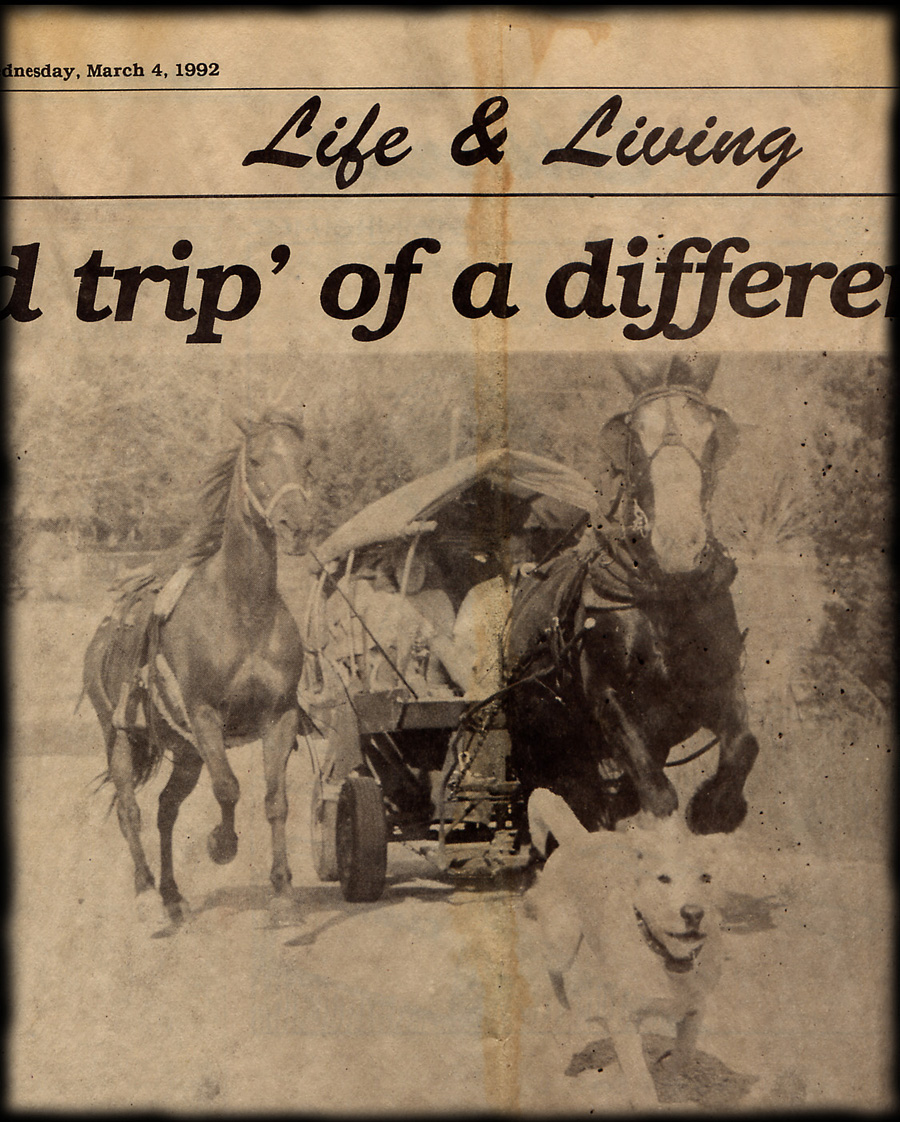

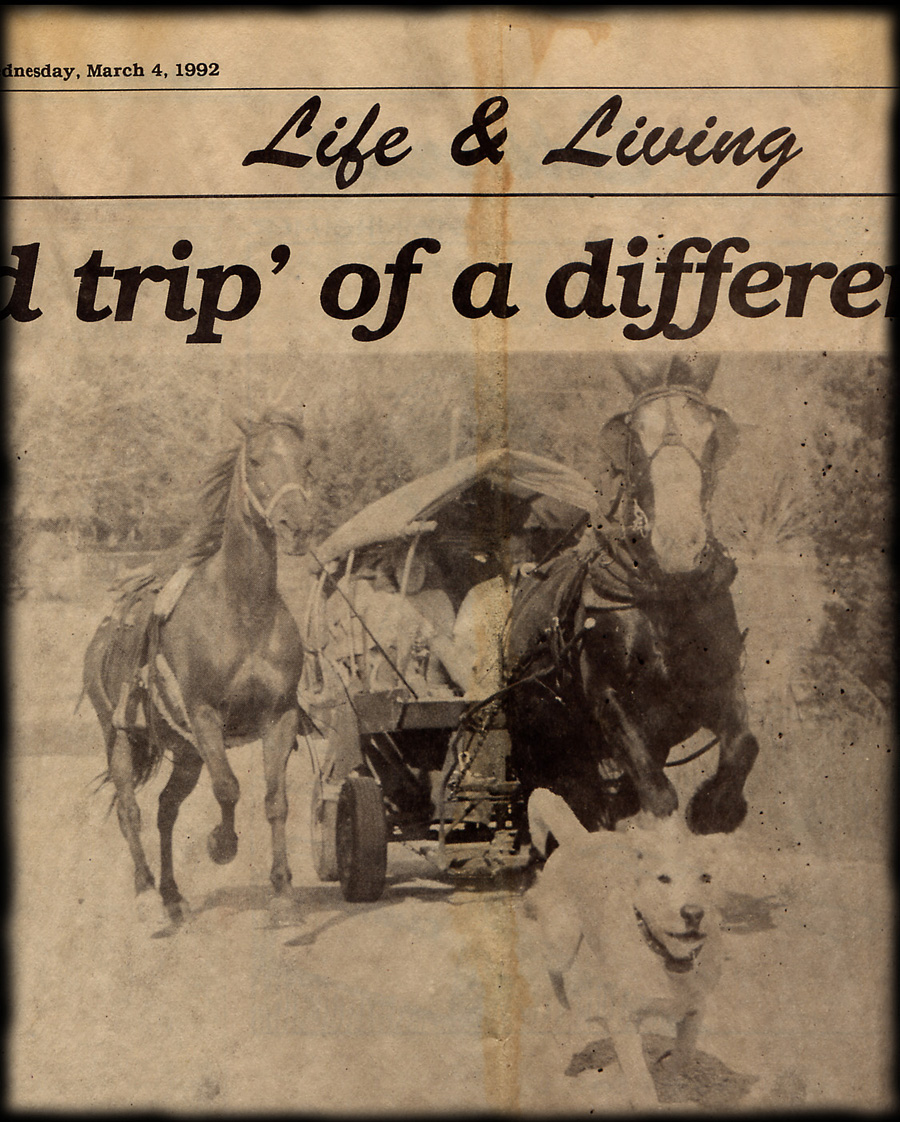

The trip of a lifetime...by horseback!

From: Plaistow, New Hampshire

To: Hoquiam, Washington

Duration: April 16, 1991 to August 11, 1994

(3 years, 4 months)

Miles: 9,000

The trip of a lifetime...by horseback!

From: Plaistow, New Hampshire

To: Hoquiam, Washington

Duration: April 16, 1991 to August 11, 1994

(3 years, 4 months)

Miles: 9,000

|

Members

of the journey: Tracy Paine, 21 years old DC Vision, 24 years old

|

|

|

Map

of trip route.

Adventure

Stories

The

Dream

The First Day

When in New York

You Can Go Your Own Way

Rescuing Rattlesnakes!

Wagons Ho?

The Misadventures of Myles

What Happened to Skidder

Texas

The Ocean

Two Becomes One

Olympic National Park

Hoquiam, End of the Trail

Slideshow & Photo Gallery

Frequently

Asked Questions

How

many miles do you travel in a day?

We traveled approximately 15 to 25 miles

a day. We rested at least 2 days per week. Sometimes we would stay in

an area for a few weeks before moving on.

What do the horses

eat?

The horses mostly grazed on grass. When there was no grass, we fed them hay.

Do you travel

on roads?

We mainly traveled along the backroads of America. Horses are not allowed

on major interstate highways, which is a good thing because Dawn is petrified

of big trucks and tractor-trailers.

Equipment

Saddles:

The saddles we

used on our journey were just conventional western saddles. However, we did

have to modify them slightly. Most western saddles have saddle strings that

are just stapled on. They are useless for tying things to the saddle. We got

7 foot long latigo strings and attached them to our saddles by drilling holes

all the way through the saddle tree and then pulling the strings through.

Our horses had chest plates to hold the saddles from sliding back.

We used string girths with stainless steel rings. At first we tried the fuzzy type, but they were slippery and caused the horses to sweat under them.

Bridles

and ropes:

Our horses did not need bridles or bits.

We only used halters with rope reins. The advantages of this were: 1) it was

more comfortable for the horse, they could forage along the way, 2) it was

more convenient to tie the horses when stopping briefly, 3) less equipment

to carry and maintain. When camping at night, we tied the horses using 75'

ropes which gave them plenty of room to move around and graze. Each rope had

a metal snap on either end. I tied a loop near one end so that we could fasten

it around the horses' necks like a collar. That way their halters could be

removed for the night. Dawn always wore a collar around her neck made of thin

rope. Sometimes I would clip a bell onto it so I could hear her movements,

especially if she was turned loose for the night.

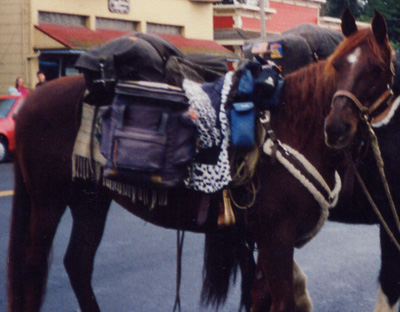

Packs:

Our journey was unique in the fact that

we did not have a packhorse. Each of us had the equipment and supplies we

needed individually on our own horse. We started out with regular canvas saddlebags.

Those lasted about a week and a half! Then we went to leather. They were heavier

and lasted just about as long. At last we tried army/navy backpacks. So far,

nothing can beat the quality and durability of these packs, not to mention

the low price and all the cool pockets! Because they are meant to be used

as backpacks, some modifications have to be made. The straps should be cut

off. A special harness made out of nylon seatbelt material is then sewn onto

each backpack using a leather-sewing awl. Seatbelt material won’t wear

out, and it is extremely strong. Next the saddle must be outfitted to accept

the modified backpacks. All that is needed is more seatbelt strapping and

some snap hooks. The following diagram shows how to make this simple saddle

harness.

The unique feature of this packing method, as opposed to conventional saddle bags, is that most of the weight of the saddlebags is shifted forward under the rider, and off the horse’s lower back and kidneys. Another great feature is that it takes less than 30 seconds to put the packs on after the horse is saddled. The packs have two ‘D’ rings on the back which hang on two small hooks that are attached to the saddle harness. So the daily routine of packing the horse is only a matter of picking up the packs and slipping the ‘D’ rings into the hooks! We kept our sleeping bags behind the saddle in an army/navy canvas duffle bag. This was attached using the saddle strings. I sewed buckles into the strings which made it easy to attach the duffle bag nice and tight so it didn’t wobble. During our journey, I would walk several miles per day with my horse. When I was walking, I would shift all my packs (the two army/navy backpacks and the duffle bag) forward onto the saddle where I would normally ride.

Dawn with packs in the 'riding' position. |

Dawn with packs moved forward in 'walking' position. |

When packing it is important to have the saddlebags well balanced. Just a pound or two off on either side can cause everything to shift to one side and rest unevenly on the horse.

Saddleblankets:

Each

horse had three blankets. The first was a standard 27" x 56" thin

blanket. This blanket was folded in half (doubled) and put on the horse first.

The great thing about using this type of blanket against the horse is that

when it gets dirty, it can be flipped over so that a new clean surface can

be put against the horse. Then when this side gets dirty, there are two more

clean sides before the blanket has to be washed. It is important to keep the

blankets clean as well as the horse in order to avoid saddle sores.

The second blanket was like the first, only narrower. This blanket draped over the horses' backs about halfway down the first saddle blanket. It served to protect the horses from the saddle bags.

The third blanket was a thick, square western saddle blanket. Ours had inserts made out of space-age material that is found in the the seats inside of the space shuttle. These inserts could be taken out and the whole blanket could be washed. The material is wonderful because it evenly distributes the weight on the horses' backs preventing any pressure points.

Supplies:

The following is a general list of supplies

that was carried on my horse:

| 75'

rope to tie Dawn out with shoeing tools camera journal/pencil/pen maps book towel 3 changes of clothes (summer or winter depending) shampoo hairbrush horsebrush toothbrush/toothpaste toilet paper sewing supplies shallow, stainless steel pan various food items lighter/matches knife flashlight tent (only when I was in Washington) sleeping bag thin wool blanket rain poncho tarp |

|

Horseshoes:

The method of shoeing I used is very similar to the conventional method, however there are a couple of little ‘tricks’ that will make shoes last longer and stay tight longer over any type of terrain, especially pavement. I have never liked using horseshoes. In fact, when I first started my horseback journey, my horse was barefoot! I had no idea how quickly a horse’s hooves could wear down when traveling on pavement (roughly 75% of the time). In less than 3 weeks, I was looking for a farrier to shoe my horse. Eventually I bought my own tools and packed them with me. Horseshoes are, at best, a necessary evil.

The

most preferable shoe I have found for long distance horseback travel is a

lightweight, flat iron shoe with no heel or toe caulks. A shoe like this will

wear paper thin and crack at the toe in only two weeks of pavement travel.

Borium is a must. This same shoe, properly coated with borium, will last one

year of pavement travel! Welding borium onto a shoe is an art as well as a

science and must be done properly to be effective. Anyone who knows how to

weld can do the job. Borium consists of tungsten carbide chunks in a brass

matrix. The shoe is preheated first. This can be done with a hot torch flame,

a forge, or even a good campfire! When the shoe is hot, borium is applied

using a torch with a low flame. If the flame is too high, the borium will

burn and pop! This stuff melts at a low temperature. The borium should be

applied in a thin single layer (not more than 1/8” thick) for the main

purpose of protecting the shoe from wear. There is no need to build the layer

of borium up thick. Borium is also very effective for riding on ice and other

slick surfaces such as parking lots coated with blacktop sealer! Because borium

affords the shoe some traction, it is advisable that a horse not used to borium

shoes be ridden on soft surfaces before riding on hard, unforgiving surfaces

so as not to cause leg injuries.

Borium and farrier supplies can be purchased at Meader

Supply, 23 Meaderboro Road, Rochester, N.H. 03867

*Note: there is an alternative to shoeing with iron shoes and nails - nylon

shoes which are applied with epoxy. I have not tried this, but I intend to

do so for my next horseback adventure. Meader Supply has these shoes.

Horseback travelers should avoid loose shoes at all costs. A loose shoe is dangerous. It is easily snagged off the hoof and very often takes part of the hoof with it. Unfortunately, loose shoes are all too common, especially for horses traveling on a daily basis, on pavement, and especially if the horse is a draft horse! The heavy weight of the draft shoe and the tremendous repetitive impact will work the shoe loose in no time. I knew of a draft horse who suffered loose shoes repeatedly and consequently lost so much hoof material that her hooves could no longer hold a shoe!

The trick to avoiding loose shoes is finishing the nails properly. Most farriers will drive a nail into the hoof wall and then ‘wring off’ the nail by using the hammer claws to twist off the sharp end of the nail close to the hoof wall. Don’t do this. Instead, bend the nail over against the hoof wall and cut it off with nail cutters. Leave 1/8” of the nail projecting from the hoof wall. When all the nails are done in this fashion, they are then seated using a ‘clinching block’ or any other piece of flat metal. Carefully file away any burrs under the nail stubs, do not create a groove in the hoof wall or file away any of the nail, as this will cause weakening. The nail stubs are then softly hammered flat against the hoof wall, and the job is done (see diagrams below). Turning the clinches in this fashion (as opposed to cutting the nail stubs short and then using alligator clinchers) will not cause tearing in the hoof wall, and they will last much longer. There is no need to smooth the clinches with a file because this will occur naturally in a couple days. A shoe nailed in this manner will stay tight for a very long time. I had shoes stay tight on my horse for 6 months straight while traveling.

| After nailing, bend point over. |

Cut

nail leaving 1/8" stub,

and seat. |

Gently, tap down nail stub. |

It

is highly advisable to use rubber rim pads when traveling by horseback whether

the travel is on pavement or in the backcountry. Rim pads do not cover the

sole of the hoof and are placed between the hoof and the shoe. They absorb

concussion and eliminate hoof and bone problems.

For more information about how to shoe horses,

refer to the book, “The Principles of Horseshoeing II” by Doug Butler.

Future

Horseback Trips

The next trip I plan to make is exclusively in the state of Idaho. The main

purpose of this trip is to see cougars in the wild. Idaho is one of the few

states in the U.S. that is home to a large number of these beautiful, elusive

cats. There are other reasons for the trip also: I need to be alone in the

quiet wilderness once again, and what better way to train my green broke young

Saddlebred stallion to ride and pack? I plan to take both him and my mare,

a veteran of the road, Dawn. I promised Dawn that I would never take her on

another long journey again - I formally retired her when her cross country

trip was over - so this will be a fairly short trip of at least two weeks

and a couple hundred miles.

The next long trip I am planning to take will be with Kilroy and perhaps another

young horse who I have yet to encounter. This trip will be for the purpose

of seeing a tiger in the wild. Therefore, we will travel through Siberia!

I will ride to Alaska and try to ferry over to the Kamchatka peninsula and

spend the summer tracking tigers. From there I may travel through China to

see yaks in their native lands, and then perhaps travel into India and see

more tigers.